Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 1 of 153 PageID# 1

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Alexandria Division

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

U.S. Department of Justice

950 Pennsylvania

Avenue NW

Washington, D

C 20530

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA

202 North Ninth Street

Richmond, VA 23219

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

455 Golden Gate Avenue, Suite 11000

San Francisco, CA

94102

STATE OF COLORADO

1300 Broadway, 7th Floor

Denver, CO 80203

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

165 Capitol

Avenue

Hartford, CT 06106

STATE OF NEW JERSEY

124 Halsey Street, 5th Floor

Newark, NJ 07102

STATE OF NEW YORK

28 Liberty Street, 20th Floor

New York, NY 10005

J

URY TRIAL DEMANDED

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 2 of 153 PageID# 2

STATE OF RHODE

ISLAND

150 South Main Street

Providence, RI 02903

and

STATE OF TENNESSEE

P.O. Box 20207

Nashville, TN 37202

Plaintiffs,

v.

GOOGLE LLC

1600 Amphitheatre Parkway

Mountain View, CA 94043

Defendant.

CO

MPLAINT

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 3 of 153 PageID# 3

Table of Contents

I.

Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1

II.

Nature of this Action

........................................................................................................... 4

III.

Display Advertising Transactions

..................................................................................... 16

A.

How Ad Tech Tools Work .................................................................................... 16

B.

How Ad Tech

Intermediaries Get Paid

................................................................. 22

C.

How Publishers and Advertisers Select Ad Tech Tools

....................................... 24

D.

Why Scale and the Resulting Network Effects are Necessary to Compete in

Ad Tech

................................................................................................................. 26

E.

How Multi-Homing Enables Competition in the

Ad Tech Stack

......................... 28

IV.

Google’s Scheme to Dominate the Ad Tech Stack

........................................................... 30

A.

Google

Buys Control of the Key Tools that

Link Publishers and Advertisers

..... 31

B.

Google

Uses

Its Acquisitions and Position Across the Ad Tech Stack to Lock

Out Rivals and Control Each Key

Ad Tech Tool

................................................. 35

1.

Google Thwarts Fair

Competition by Making I

ts Google Ads’

Advertiser Demand Exclusive to Its Own Ad Exchange, AdX

................ 37

2.

In Turn, Google Makes

Its Ad Exchange’s Real-Time Bids Exclusive

to Its Publisher Ad Server

......................................................................... 43

3.

Finally, Google Uses

Its Control of Publisher

Inventory to Force More

Valuable Transactions Through Its

Ad Exchange

.................................... 46

4.

Google’s Dominance Across the Ad Tech Stack Gives

It the Unique

Ability to Manipulate Auctions to Protect Its Position, Hinder Rivals,

and Work Against

Its Own Customers’

Interests

..................................... 55

a)

Google Works Against the

Interests of

Its Google Ads’

Customers By Submitting Two Bids

Into AdX

Auctions

............. 57

b)

Google Manipulates

Its Fees to Keep More High-Value

Impressions Out of the Hands of Rivals

....................................... 60

C.

Google

Buys and Kills a Burgeoning Competitor and Then Tightens the

Screws

................................................................................................................... 65

1.

Google Extinguishes AdMeld’s Potential Threat

..................................... 65

2.

Google Doubles Down on Preventing Rival Publisher Ad Servers from

Accessing AdX

and Google Ads’ Demand

.............................................. 68

3.

Google Manipulates Google Ads’ Bidding Strategy

to Block Publisher

Partnerships with Rivals

........................................................................... 71

D.

Google Responds to the Threat of Header

Bidding by

Further

Excluding

Rivals and Reinforcing I

ts Dominance

................................................................. 72

i

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 4 of 153 PageID# 4

1.

The

Industry Attempts to Rebel Against Google’s

Exclusionary

Practices

....................................................................................................

72

2.

Google

Blunts Header

Bidding B

y “Drying Out” the Competition

.........

78

a)

Google

Develops So-Called Open Bidding, Its Own Google-

Friendly Version of Header Bidding To Preserve

Its Control

Over the Sale of Publisher

Inventory

............................................

78

b)

Google

Further Stunts Header

Bidding by Working to Bring

Facebook and Amazon into Its Open Bidding Fold......................

82

c)

Google Manipulates

Its Publisher Fees Using

Dynamic

Revenue Sharing in Order to Route More Transactions

Through Its Ad Exchange and Deny Scale to Rival Ad

Exchanges Using Header Bidding

................................................

86

d)

Google

Launches Project Poirot to Manipulate

Its

Advertisers’

Spend to “Dry Out” and

Deny Scale to Rival Ad

Exchanges

That

Use Header

Bidding..............................................................

90

e)

Google

Imposes So-Called Unified Pricing Rules

to Deprive

Publishers of Control and Force More Transactions Through

Google’s Ad Exchange

...............................................................

101

f)

Google

Outright Blocks the Use of Standard Header Bidding

on Accelerated Mobile Pages......................................................

110

g)

Google Replaces

Its

Last

Look Preference from Dynamic

Allocation with an Algorithmic Advantage and Degrades

Data

Available to Publishers

...............................................................

113

V.

Anticompetitive Effects

..................................................................................................

116

VI.

Relevant Markets

............................................................................................................

123

A.

Geographic Markets

............................................................................................

124

B.

Product Markets

..................................................................................................

124

1.

Publisher Ad Servers...............................................................................

124

2.

Ad Exchanges

.........................................................................................

126

3.

Advertiser Ad Networks

.........................................................................

129

VII.

Jurisdiction, Venue, and Commerce

...............................................................................

131

VIII.

Violations Alleged

..........................................................................................................

132

IX.

Request for Relief

...........................................................................................................

139

X.

Demand for

a Jury Trial

..................................................................................................

140

ii

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 5 of 153 PageID# 5

I.

INTRODUCTION

1.

An open, vibrant internet is indispensable to

American life. But today’s internet

would not exist without

the

digital

advertising revenue that, as a practical

matter, funds

its

creation and expansion. The internet provides the public with unprecedented access to ideas,

artistic expression,

news, commerce,

and services. Content creators

span

every conceivable

industry; they publish diverse

material on countless websites that inform, entertain, and connect

society in vital ways. Yet the viability of many of these

websites depends on their ability to sell

digital advertising

space. Just as newspaper, radio, and television organizations

historically

relied

on advertising to fund their operations, today’s online publishers

likewise rely on

advertising

revenue to support their

activities and reach. But unlike

historical me

dia

advertising, today’s

online ads are bought

and sold in enormous volumes in mere fractions of

a second, using highly

sophisticated tools and automated exchanges that

more closely resemble a modern stock

exchange than an old-fashioned, bilateral contract

negotiation for newspaper

ad space.

2.

Website publishers

in the United States sell more than

5 trillion digital display

advertisements

on the open web each year—or more than 13 billion advertisements

every day.

The sheer volume of these online ads make the

offline advertisements

of yesteryear

pale in

comparison. To put these numbers in perspective, the daily volume of digital display

advertisements

grossly

outnumbers (by several multiples) the average number of stocks traded

each day on the New York Stock Exchange. The digital display

advertising bus

iness is also

lucrative.

Collectively,

these

advertisements

generate more than $20 billion

in revenue

per

year,

just for publishers based in the

United States.

3.

To meet this demand, sophisticated technological tools, informally

known as “ad

tech,” have developed to automate advertising

matchmaking between two key

groups:

website

1

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 6 of 153 PageID# 6

publishers and

advertisers.

1

These tools have evolved such that today, every time an internet user

opens a webpage with ad space to sell, ad tech tools almost instantly match that website

publisher with an advertiser looking to promote its products or services to the website’s

individual user. This process typically involves the use of an automated advertising exchange

that runs a high-speed auction designed to identify the best match between a publisher selling

internet ad space and the advertisers looking to buy it.

4. But competition in the ad tech space is broken, for reasons that were neither

accidental nor inevitable. One industry behemoth, Google, has corrupted legitimate competition

in the ad tech industry by engaging in a systematic campaign to seize control of the wide swath

of high-tech tools used by publishers, advertisers, and brokers, to facilitate digital advertising.

Having inserted itself into all aspects of the digital advertising marketplace, Google has used

anticompetitive, exclusionary, and unlawful means to eliminate or severely diminish any threat

to its dominance over digital advertising technologies.

5. Google’s plan has been simple but effective: (1) neutralize or eliminate ad tech

competitors, actual or potential, t hrough a series of acquisitions; and (2) wield its dominance

across digital advertising markets to force more publishers and advertisers to use its products

while disrupting their ability to use competing products effectively. Whenever Google’s

customers and competitors responded with innovation t hat threatened Google’s stranglehold over

any one of these ad tech tools, Google’s anticompetitive response has been swift and effective.

Each time a threat has emerged, Google has used its market power in one or more of these ad

1

Internet advertisers include businesses, agencies of federal and state governments, charitable

organizations, political candidates, public interest groups, and more. The money these advertisers

spend on digital advertising creates an important stream of revenue for websites to use in

creating, developing, and publishing website content.

2

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 7 of 153 PageID# 7

tech tools to quash the threat.

The result:

Google’s plan for

durable, i

ndustry-wide

dominance

has

succeeded.

6.

Google, a

single company

with pervasive conflicts of interest, now

controls:

(1)

the

technology

used by

nearly every major

website publisher to offer

advertising

space

for

sale;

(2)

the

leading tools used by

advertisers

to buy

that advertising

space; and (3)

the

largest ad

exchange

that matches publishers

with

advertisers

each time that

ad space is sold. Google’s

pervasive power over

the entire

ad tech

industry

has

been

questioned by its own digital

advertising executives, at least one of whom

aptly begged t

he question:

“[I]s there a deeper issue

with us owning the platform, the exchange, and a

huge network? The analogy would be if

Goldman or Citibank owned the NYSE.”

7.

By deploying opaque

rules that benefit itself and harm rivals,

Google

has wielded

its

power

across the ad tech industry

to dictate how

digital advertising is sold, a

nd the

very terms

on which its rivals can compete.

Google

abuses

its

monopoly

power to disadvantage

website

publishers and advertisers

who dare

to use

competing ad tech products

in a search for

higher

quality, or

lower cost,

matches. Google uses its

dominion ove

r

digital advertising technology

to

funnel

more transactions

to its

own

ad tech

products

where

it

extracts

inflated

fees

to line its own

pockets at the expense of

the advertisers

and publishers

it purportedly serves.

8.

Google’s anticompetitive behavior has

raised barriers to entry to artificially

high

levels,

forced

key competitors

to abandon

the market

for ad tech tools, dissuaded

potential

competitors

from joining the

market,

and

left

Google’s

few

remaining competitors

marginalized

and unfairly disadvantaged. G

oogle has thwarted meaningful competition and deterred

innovation in the digital advertising industry, taken

supra-competitive

profits for itself, and

3

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 8 of 153 PageID# 8

prevented

the free market

from

functioning

fairly

to support the interests of

the advertisers and

publishers who make today’s powerful internet possible.

9.

The harm is clear: website creators earn less, and advertisers pay more, than they

would in a market

where unfettered competitive pressure could discipline prices and lead to more

innovative ad tech tools

that would ultimately result in higher quality

and lower cost transactions

for market participants. And this conduct hurts all of us because, as publishers make less money

from

advertisements, fewer publishers are able to offer internet content without subscriptions,

paywalls, or alternative forms of monetization.

One troubling, but revealing, statistic

demonstrates the point: on average, Google

keeps

at least

thirty

cents—and sometimes

far

more—of

each

advertising

dollar

flowing f

rom advertisers to website publishers through

Google’s

ad tech

tools. Google’s

own

internal documents concede

that Google

would earn far

less in a competitive market.

10.

The United States

and Plaintiff States bring this action for violations of the

Sherman Act to halt Google’s

anticompetitive scheme, unwind Google’s monopolistic grip on

the market, and

restore

competition to digital advertising.

II.

NATURE

OF THIS ACTION

11.

The seeds for

Google’s

eventual

march toward a

monopoly

in ad tech

were sown

in the early 2000s, when it

capitalized on its

well-known search engine to start a profitable

search

advertising business. In 2000, Google launched Google Ads

(then called AdWords

2

), a

tool that allowed businesses to buy advertisements that could be seen by Google search users

right alongside Google’s popular search engine results. Businesses quickly learned the power of

2

Over the period addressed by the Complaint, Google has renamed its ad tech products a number

of times and has either shifted certain functions between products or combined its products in

ways intended to obscure Google’s dominance across the ad tech stack.

4

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 9 of 153 PageID# 9

this

instantaneous, highly-targeted

advertising

technique,

and

they

flocked to Google Ads

as a

result.

12.

By the early 2000s, Google realized that these

same advertisers

would buy

digital

advertisements

on third-party websites

as well. S

o Google

stepped in to profit (as a middleman)

on digital advertising transactions having nothing to do with Google or its

search engine

by

creating

an advertiser ad tech tool

for Google Ads’ customers

that wanted

to buy ad space on

third-party websites.

13.

But Google

was not satisfied with its dominance on the

advertising

side of the

industry

alone; Google

devised a plan to build a

moat around the emerging ad tech industry by

developing a

tool that would be used by website

publishers

as well.

14.

Google

sought to develop an ad tech tool called a publisher ad server

that

publishers

would use

to manage their

online advertising sales. Google recognized that

because

publisher ad servers set the rules for how and to whom publisher advertising opportunities are

sold, ow

ning a publisher

ad server was key to having visibility into, a

nd control over,

the

publisher side

of digital advertising.

By controlling the

publisher

ad server

on the other end of

the transaction, Google

could further entrench its

advertiser

customer

base

by giving advertisers

access to more advertising opportunities and pushing

more transactions

their way.

15.

Of course,

by becoming the dominant player on both sides of the digital

advertising industry, Google

could

also

play both sides against the middle. It

could c

ontrol both

the publishers

with

digital ad space to

sell,

as well

as the

advertisers who want to buy that space.

With influence over advertising transactions

end-to-end, Google realized it could

become “the

be-all, and end-all location for all ad serving.”

The

outsized

influence it

could obt

ain by having a

dominant position on bot

h sides of the industry

would give

Google the ability to charge

supra-

5

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 10 of 153 PageID# 10

competitive fees

and also enjoy

an

abiding dominance sufficient

to exclude rivals

from

competition. Google would no longer have to compete on the merits; it could simply set the rules

of the game to exclude rivals.

16.

The only problem with Google’s plan was that Google’s publisher ad server failed

to gain traction in the industry. So, Google

pivoted to

acquiring

the market-leading publisher ad

server from an

ad tech firm called

DoubleClick. In early 2008, Google

closed its acquisition of

DoubleClick for over $3 billion. Through the

transaction, Google acquired a publisher ad server

(“DoubleClick for Publishers” or “DFP”), which had a 60% market share

at the time. It

also

acquired

a nascent

ad exchange

(“AdX”) through which digital advertising space could be

auctioned. The DoubleClick acquisition vaulted Google

into a

commanding position over

the

tools publishers use to sell advertising opportunities, complementing

Google’s existing tool for

advertisers, Google Ads, and set the stage for Google’s later exclusionary conduct

across the ad

tech industry.

17.

After the DoubleClick acquisition, Google enhanced and entrenched DFP’s

already-dominant market position. Google

internally

recognized that publisher ad servers

are

“sticky” products, meaning that publishers rarely

switch because of the high costs and risks

involved. As

DoubleClick’s former

CEO observed, “Nothing has such high switching costs. . . .

Takes an act of God to do it.” Thus, in order to lock more publishers into DFP and to reinforce

its stickiness, Google forged an exclusive link between Google

Ads

and

DFP through the

AdX

ad exchange. If publishers wanted access to exclusive Google Ads’ advertising demand, they had

to use Google’s publisher ad server

(DFP)

and

ad

exchange

(AdX), rather than equivalent tools

offered by Google’s

rivals. In effect,

Google

positioned itself to function simultaneously

as

buyer, seller, and auctioneer of digital display

advertising.

6

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 11 of 153 PageID# 11

18.

Google’s

strategy paid off. This arrangement

has

had a profound effect on the

evolution of

digital

advertising. First, it tilted the industry in Google’s favor, driving publishers

to adopt and stay on Google’s

DFP

publisher ad server

in order to have access to Google

Ads’

advertiser demand. Second, it

cut off the possibility that Google Ads’

advertiser spending could

sustain, or encourage the

entry of, a rival ad exchange or publisher ad server by providing c

ritical

advertising demand. For

the vast majority of

webpage

publishers, this arrangement made DFP

the only realistic publisher ad server option. Indeed, by 2015, Google estimated

that

DFP’s

publisher

ad server

market

share had grown to a remarkable 90%. Google’s durable monopoly

over the publisher ad server market

has

allowed it to avoid innovation and competition by

controlling

the very rules

by which the

game is played. As a result, other publisher ad servers

have left the market

altogether, refocused on related

markets, or faded into insignificance; no

new publisher ad servers

have entered

the market.

19.

Around

the same time

that

Google

tied

its

exclusive Google Ads’

advertiser

demand to its publisher ad server

(DFP)

through AdX,

Google

took two additional steps to make

it more difficult for rivals to compete.

20.

First, Google configured Google

Ads to bid on Google’s

AdX ad exchange in a

way that actually

increased

the price of advertising, to the benefit of publishers and the detriment

of Google’s own advertiser customers. As one Google

employee observed, Google

Ads was

effectively sending a “$3bn

yearly check

[to publishers]

by overcharging our advertisers to

ensure we’re strong on the pub[lisher] side.”

In the short-term, this conduct

locked publishers

into Google’s

publisher

ad server

by providing them

a steady

stream of

intentionally-inflated

prices for certain

inventory,

at the cost of Google’s own advertiser

customers. B

ut in the long

run, Google’s actions harmed publishers

as well

by driving out

rival publisher ad servers

and

7

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 12 of 153 PageID# 12

limiting competition in the publisher ad server market. In effect, Google

was robbing from Peter

(the advertisers) to pay Paul (the publishers), all the while collecting a hefty

transaction fee for

its own privileged position in the middle. T

his conduct turned

the entire purpose

of the digital

advertising industry

on its head. Rather than

helping to

fund website publishing, Google

was

siphoning

off

advertising dollars for itself through the imposition of

supra-competitive

fees

on its

platforms. A

rival publisher ad server

could not compete with Google’s inflated ad prices,

especially without access to Google’s captive

advertiser demand from Google Ads.

21.

Second,

Google used its captive advertiser demand to

thwart legitimate

competition by

giving

its AdX ad exchange

an a

dvantage over other

ad exchanges through

a

mechanism known as

dynamic allocation. Dynamic allocation

was a means by which

Google

manipulated its publisher ad server to give

the

Google-owned AdX (and

only AdX) the

opportunity to buy publisher inventory before it was offered to any other

ad exchange, a

nd often

to do so at artificially low prices. Google

also

programmed

DFP, its

publisher ad server, t

o

prevent

publishers

from

offering

preferential terms to other ad exchanges or allowing

those

exchanges to operate i

n the same way

with DFP.

Google

knew

that dynamic allocation

would

inevitably

steer advertising transactions

away from rivals, denying them critical scale needed to

compete, and would advantage

AdX,

where Google could extract the largest fees.

Google’s

scheme p

redictably reinforced publishers’ dependence on both AdX

and DFP. P

ublishers

were

effectively precluded from using rival ad servers

or ad exchanges that might better suit their

needs

while Google

was

given a free pass from having to compete on the merits with those

rivals.

22.

By at least

2010, other ad tech companies

had

recognized that Google’s platforms

were not working in the

best interest of publishers, a

nd they attempted to develop innovative

8

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 13 of 153 PageID# 13

technologies to introduce more competition. Some companies began offering “yield

management”

functionality that helped publishers identify

on a real-time basis

better prices for

their inventory outside of Google’s products. Google recognized

that yield managers posed a

major threat to the increasingly closed system Google sought to establish, in which

only

its ad

exchange was able to

compete based on

real-time pricing.

So, in response, Google

employed a

familiar tactic: acquire, then extinguish, any

competitive threat.

23.

In 2011, Google

acquired

AdMeld, the leading

yield manager,

folded its

functionality

into Google’s existing products, a

nd then

shut down its

operations

with non-Google

ad

exchanges and

advertiser tools. Google

soon thereafter

changed

its AdX contract terms to

prohibit publishers from using any other platform

(such as

another

yield manager) that would

force

AdX to compete in

real

time with other ad exchanges. As

a Google

product manager

wrote:

“Our

goal should be

all or nothing

–

use AdX as

your [exchange] or don’t

get access to our

[advertising]

demand.”

Unsurprisingly, this unabashed, a

nticompetitive conduct had a profound

effect on the market, denying rival ad tech competitors the scale necessary to compete and

depriving publishers the benefits of free market competition and real choice.

24.

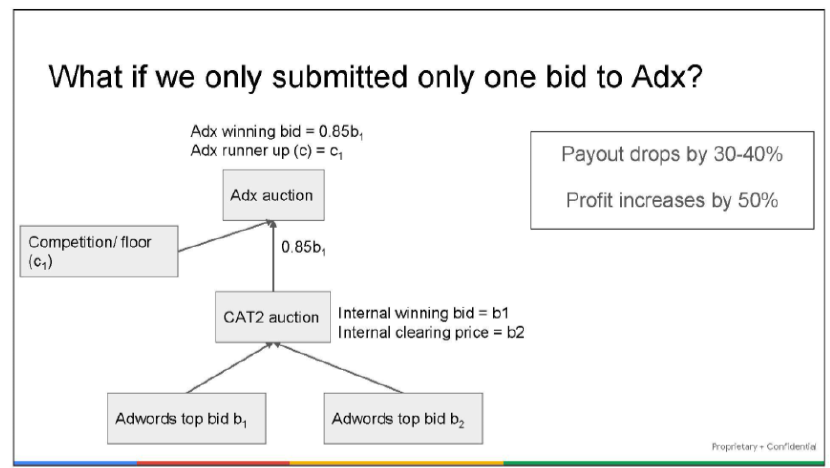

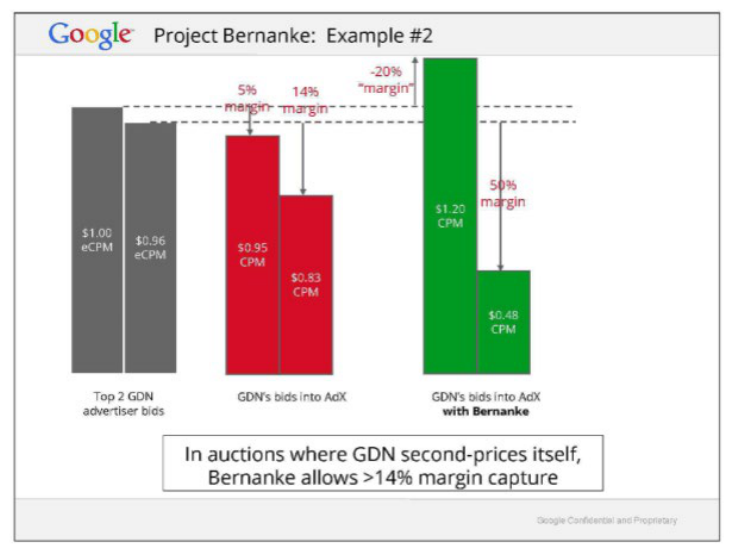

Not long after, in 2013, Google launched Project Bernanke, a

secret

scheme to

manipulate the bids that Google

Ads submitted into Google’s

ad exchange, AdX, in order to win

more competitive transactions and solidify AdX’s dominance

in the industry.

Project Bernanke

allowed

Google

to suppress competition by

preventing rival

ad

exchanges

from achieving the

transaction volume and scale necessary to compete. Unless another ad e

xchange developed both

its own unique source of

captive advertiser demand—where it could potentially

manipulate

advertiser bids—and a widely-adopted publisher

ad server—where it could see the same

advertising inventory

and bid data as Google—competition

on the same terms as Google was

9

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 14 of 153 PageID# 14

nearly impossible. Once again, by controlling all sides of the ad tech industry, Google has been

able to manipulate the system in ways unique to itself so that, in the end, it did not have to

compete on the merits for customers and volume.

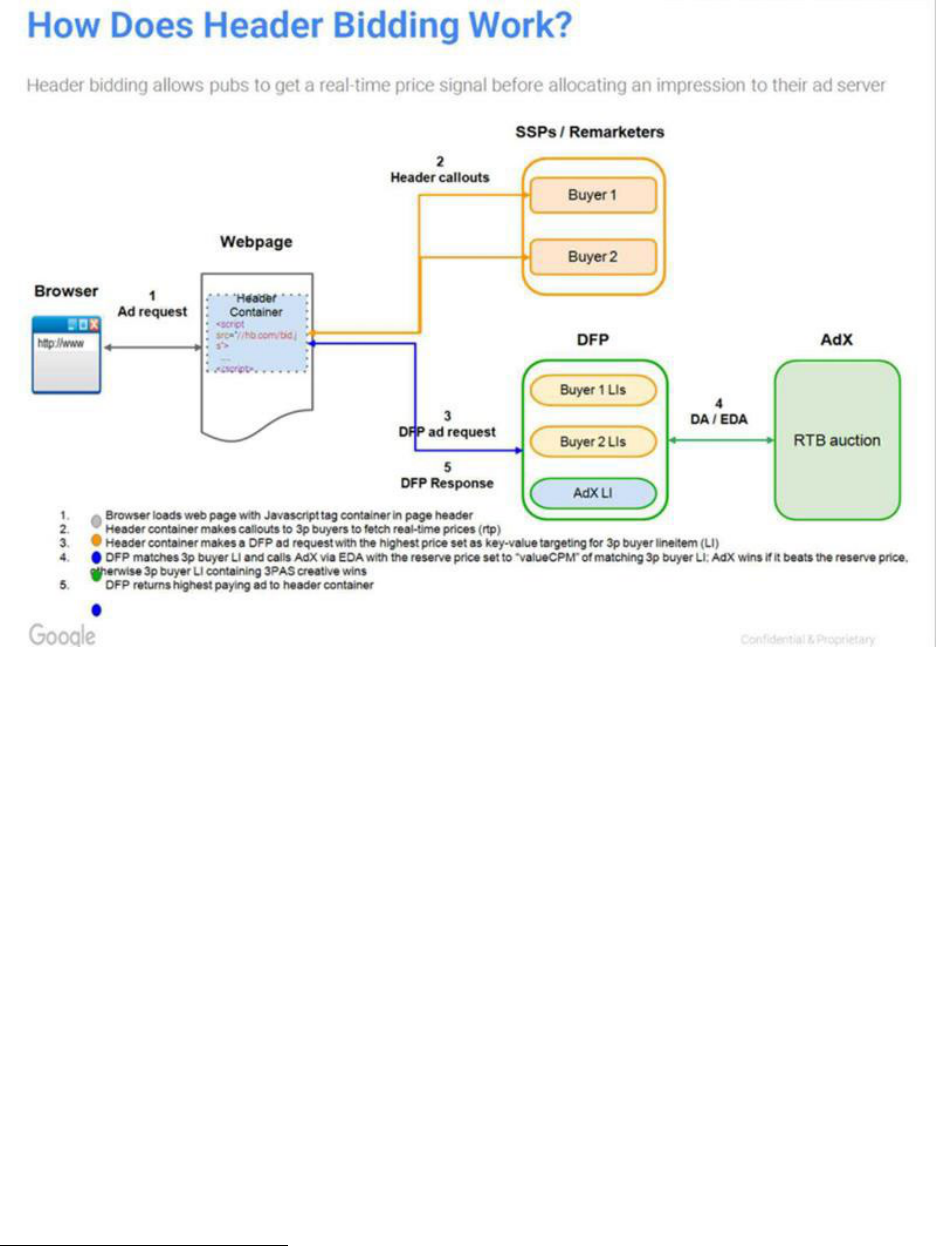

25. Publishers and competing ad tech providers, increasingly wary of Google’s

bullying behavior, have continued to look for new ways to circumvent Google’s dominance.

Between 2012 and 2013, market participants began using a technique called “header bidding”

as a partial workaround to Google’s self-preferential algorithms and ad tech restrictions. As one

Google employee explained, “Publishers felt locked-in by dynamic allocation in [Google’s ad

server] which only gave [Google’s ad exchange] the ability to compete, so HB [header bidding]

was born.”

26. Publishers used header bidding to take back some degree of power over their own

advertising transactions. They inserted header bidding computer code onto their own websites to

allow non-Google advertising exchanges an opportunity to bid for advertising inventory before

Google’s hard-coded preferences for its own ad exchange were triggered. Header bidding

allowed publishers to ensure that multiple advertising exchanges—not just Google’s AdX—

could bid on their inventory, thereby increasing the chances that they could find the best match.

27. Google has refused to tolerate this new form of competition, even though it has

acknowledged in internal emails that header bidding had grown naturally out of Google’s being

“unwilling[] to open our systems to the types of transactions, policies and innovations that

buyers and sellers wish to transact.” Indeed, Google privately admitted that “header bidding and

header wrappers are BETTER than [Google’s platforms] for buyers and sellers,” and that

increased competition between AdX and publishers using header bidding would increase

publisher revenues by 30 to 40%, and would provide additional transparency to advertisers. Not

10

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 15 of 153 PageID# 15

only would header bidding enable rival exchanges to compete more effectively against Google’s

ad exchange, it might also allow them or others to enter the publisher ad server market if Google

no longer had exclusive access to unique advertiser demand.

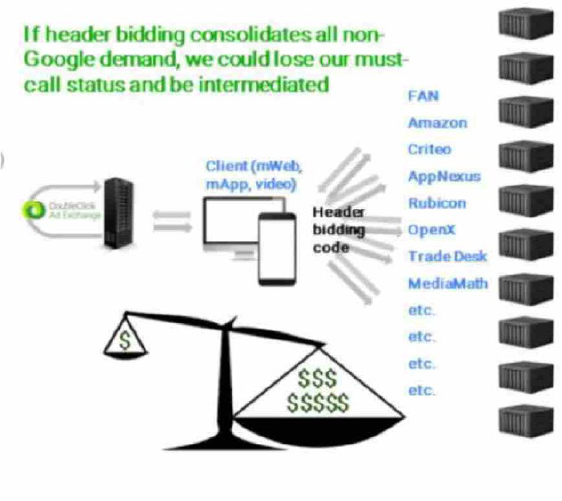

28. Google executives described header bidding as an “existential threat.” They

worried that wider adoption of header bidding practices could lead to Google’s ad exchange

having to compete with other ad exchanges on a level playing field, where Google could no

longer set the rules in its own favor. If that were to happen, those rival ad exchanges might

actually succeed in eroding, or even breaking up, Google’s advertiser juggernaut, and the entire

industry could be opened up for competition. Google feared the worst: the entire moat of

anticompetitive protections that Google had built around the ad tech industry could be breached.

29. Faced with this “existential” threat, Google sought to stem the rising tide toward

header bidding by promoting a Google-friendly analog of header bidding that Google

deceptively titled “Open Bidding.” Google has promoted Open Bidding as an answer to the

industry’s call for wider participation by rival ad exchanges and increased competition. In fact,

Open Bidding was a Trojan Horse that Google used to further cement its own monopoly power.

30. As a condition to using Google’s Open Bidding, Google has required that

publishers and participating ad exchanges give Google visibility into each auction (including

how rival exchanges bid), allow Google to extract a sizeable fee on every transaction (even

where another exchange won), and limit the pool of advertisers allowed to bid in the auctions. In

doing so, Google’s ad exchange has retained a guaranteed seat in every auction, regardless of

whether Google’s ad exchange offers the best match between advertisers and publishers.

31. Google also sought to co-opt what it perceived to be its two biggest threats

(Facebook and Amazon) into Open Bidding. In internal documents, Google concluded that while

11

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 16 of 153 PageID# 16

it “[c]annot avoid competing with FAN [Facebook],” it could, through a deal with Facebook,

“build a moat around our demand.” Internal documents recommending a deal with Facebook

revealed Google’s primary motive: “[f]or web inventory, we will move [Facebook’s] demand off

of header bidding set up and further weaken the header bidding narrative in the marketplace.”

Thus, for these reasons, Google ultimately agreed to provide preferential Open Bidding auction

terms to Facebook in exchange for spend and pricing commitments designed to push more of

Facebook’s captive advertiser spend onto Google’s platforms. Google sought to head off

Amazon’s investment in header bidding technology with a similar offer, albeit without the same

success.

32. Google also adjusted its auction mechanisms across its ad tech products to divert

more transactions to itself and away from rivals that might deploy header bidding. On the

publisher side, Google allowed AdX—and only AdX—to change its auction bid by altering

Google’s own fee after seeing the price to beat from another exchange.

33. On the advertiser side, Google first considered outright blocking its advertiser

buying tool from buying inventory made available via header bidding. The goal: “dry out HB

[header bidding].” When Google decided that strategy would be too costly for Google, it pivoted

to a different and more insidious strategy with the same effect.

34. Google recognized that “instead of stop[ping] bidding on HB [header bidding]

queries, we could bid lower on HB queries,” and win the same impressions on Google’s ad

exchange instead. No rival exchange was in a position to compete with this strategy because no

rival had the scale necessary to compete against the industry giant, especially considering the

built-in advantages that Google afforded its own ad exchange and publisher ad server. Google,

and Google alone, had control over both the leading source of advertiser demand and the

12

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 17 of 153 PageID# 17

dominant publisher ad server. So, Google programmed its advertiser buying tool to advantage its

ad exchange.

35. Google’s bidding strategy on header bidding transactions proved remarkably

effective in stunting the growth of header bidding, but Google still worried that its moat was not

fully secure. Google learned that some publishers were using price controls within Google’s own

DFP publisher ad server to sell advertising inventory to rival exchanges outside of Google’s

closed-wall system, even in instances where Google’s own AdX exchange had offered to pay

more for the inventory. Publishers did so for a variety of reasons, including considerations

related to ad quality, volume discounts, diversification of demand sources, data asymmetries, or

other factors.

36. When Google identified this threat, it simply removed the feature from DFP and

instead imposed competition-stifling Unified Pricing Rules. Under these new rules, publishers

could no longer use price floors to choose rival exchanges or other buyers over AdX or Google

Ads, no matter the reason. Google effectively took away their own customers’ right to choose

what buyer or ad exchange best suited their needs. In doing so, Google once again bought itself a

free pass on competition.

37. Google’s exclusionary, anticompetitive acts have severely weakened, if not

destroyed, competition in the ad tech industry. In decision after decision, year after year, Google

has repeatedly done what was necessary to vanquish competitive threats, including by enacting

policies that took choices away from its own customers. And despite what Google may claim, it

did not do so to protect the privacy interests of Google users. Indeed, Google intentionally

13

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 18 of 153 PageID# 18

exploited its massive trove of user data to further entrench its monopoly across the digital

advertising industry.

3

38. Due to Google’s conduct, ad tech tools that should have evolved to better serve

website publishers and advertisers in a competitive environment have instead evolved to serve

the interests of Google alone, to the detriment of Google’s own customers. The results have been

catastrophic for competition. Today, major website publishers have a single viable choice for

publisher ad servers—Google’s DoubleClick for Publishers. Google routes transactions from its

publisher ad server to its more expensive ad exchange—AdX—and away from rival platforms,

all of which are less than a quarter of AdX’s size.

39. Advertisers and publishers, the key players in this market, have had scant

visibility into the scope and extent of Google’s anticompetitive conduct. As the lone conflicted

representative of both buyers and sellers, Google has created a deliberately-deceptive black box

where Google sets the auction rules to its own advantage. Diminished competitive pressure has

reduced Google’s incentive to innovate, and Google’s control of these key ad tech tools has

inhibited rivals’ ability to introduce efficiency-enhancing innovations. Publishers and advertisers

suffer from reduced competition for both ad tech products and advertising inventory. Google’s

conduct undermines the very purpose of digital advertising in the first place: to achieve optimum

terms and pricing for digital advertisements so website publishers can continue to serve their

3

At the time of the DoubleClick acquisition, Google’s privacy policies prohibited the company

from combining user data obtained from its own properties, e.g., Search, Gmail, and YouTube,

with data obtained from non-Google websites. But in 2016, as part of Project Narnia, Google

changed that policy, combining all user data into a single user identification that proved

invaluable to Google’s efforts to build and maintain its monopoly across the ad tech industry.

Over time, Google used this unique trove of data to supercharge the ability of Google’s buying

tools to target advertising to particular users in ways no one else in the industry could absent the

acquisition of monopoly—or at least dominant—positions in adjacent markets such as Search.

14

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 19 of 153 PageID# 19

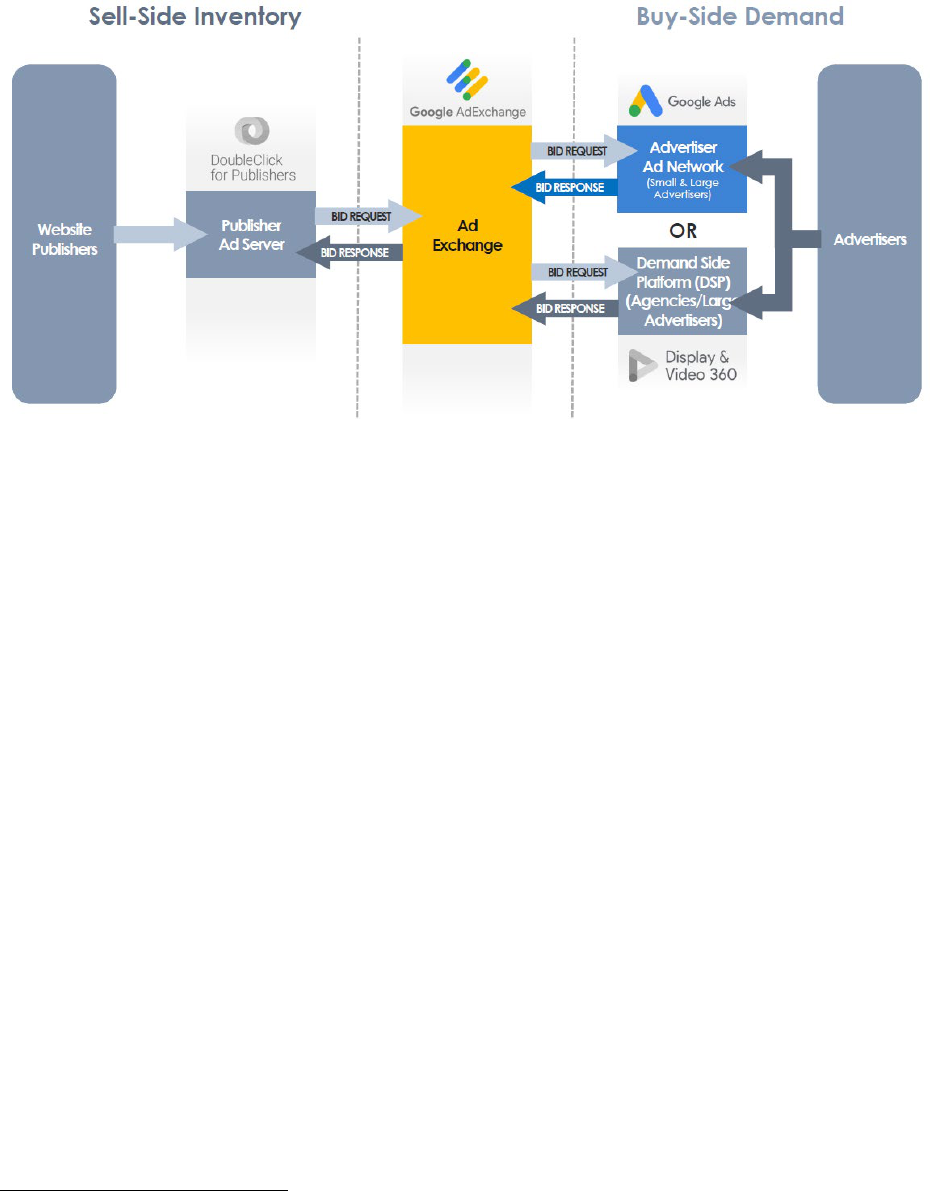

vital purposes in society. Indeed, Google’s own documents show that Google has siphoned off

thirty-five cents of each advertising dollar that flows through Google’s ad tech tools:

Fig. 1

40. The cumulative impact of Google’s anticompetitive conduct is more than simply

the sum of each harm Google has caused. As new threats have arisen, Google has spread its

actions across wide-ranging ad tech products knowing the synergistic, multiplier effect that its

actions would have across the industry. Because Google has such a powerful hand in each aspect

of the ad tech industry, it alone has the power to use and deploy hidden levers to manipulate the

overall system to its advantage.

41. It is critical to restore competition in these markets by enjoining Google’s

anticompetitive practices, unwinding Google’s anticompetitive acquisitions, and imposing a

remedy sufficient both to deny Google the fruits of its illegal conduct and to prevent further harm

to competition in the future. Absent a court order for the necessary and appropriate relief, Google

will continue to fortify its monopoly position, execute its anticompetitive strategies, and thwart

15

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 20 of 153 PageID# 20

the competitive process,

thereby raising

costs, reducing c

hoice, and stifling innovation in this

important industry.

III.

DISPLAY ADVERTISING

TRANSACTIONS

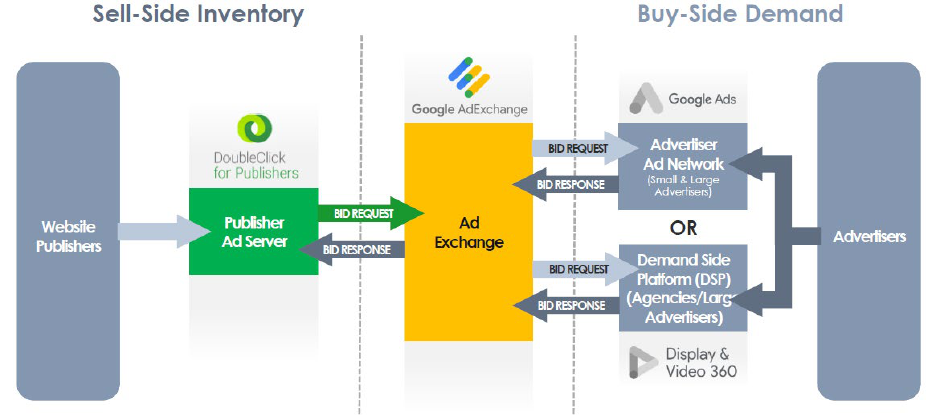

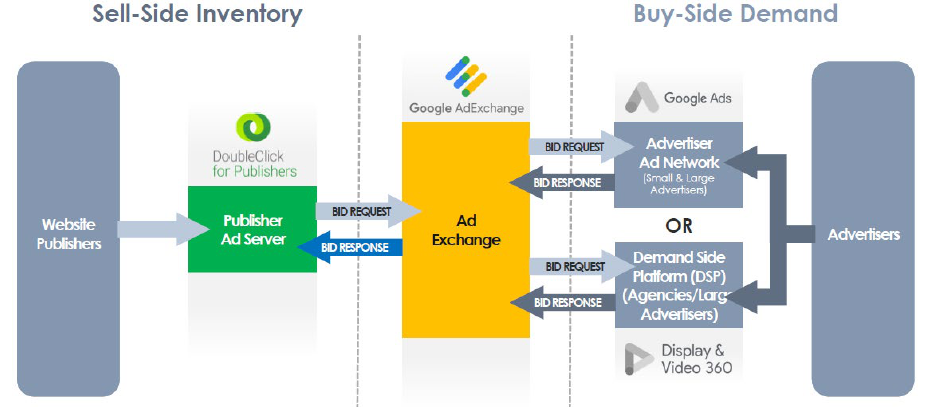

42.

When an internet user opens a website,

a complex series of transactions—nearly

instantaneous and invisible to the user—determines which ad to show to that user in each

available ad space on the

webpage. The set of technological tools that connect

website publishers

selling

advertising opportunities to the advertisers

wishing to buy those advertising opportunities

(“ad inventory”)

is referred to as

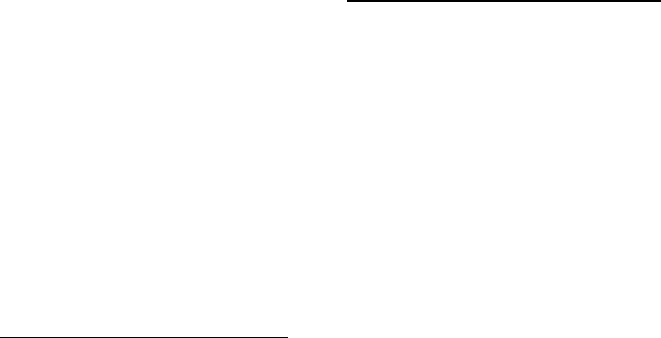

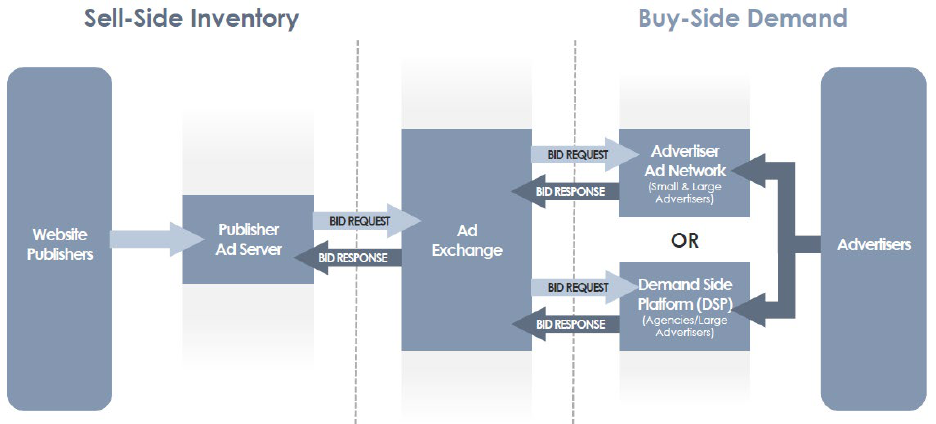

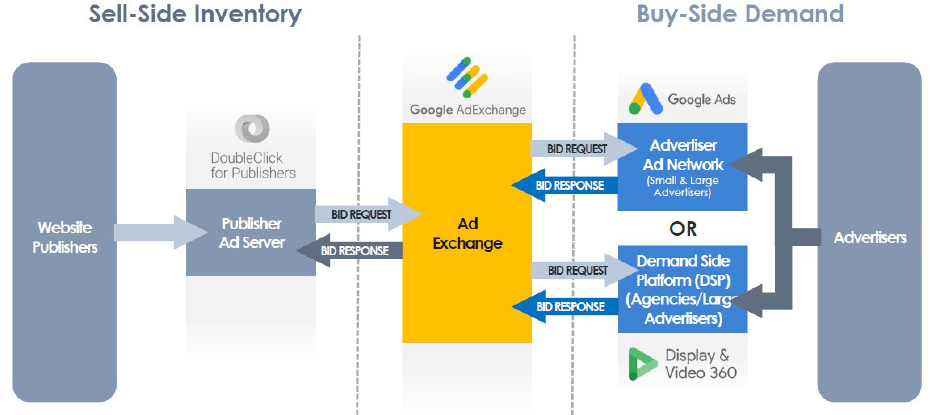

ad tech. Below is a schematic depicting

some of the important

ad tech tools used in online digital advertising:

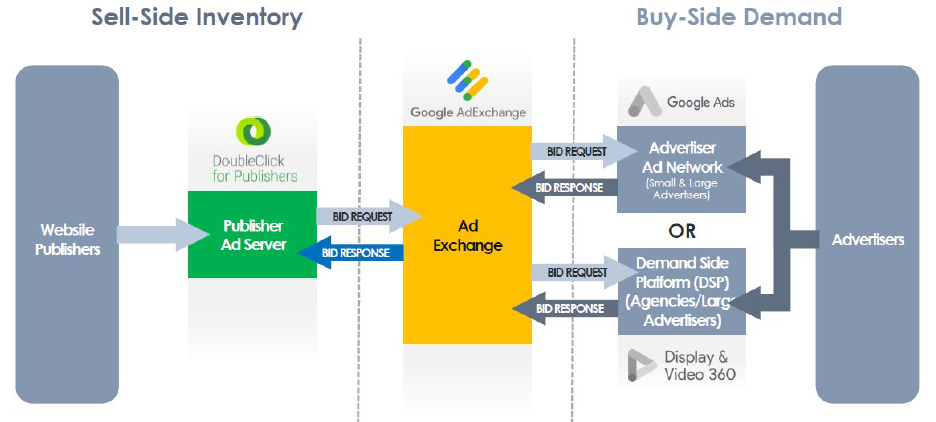

Fig. 2

A. How Ad Tech Tools Work

4

43. The content creator or owner of a website is called a publisher. Each website can

be programmed by its publisher to create slots where ad s can be displayed. A graphical ad

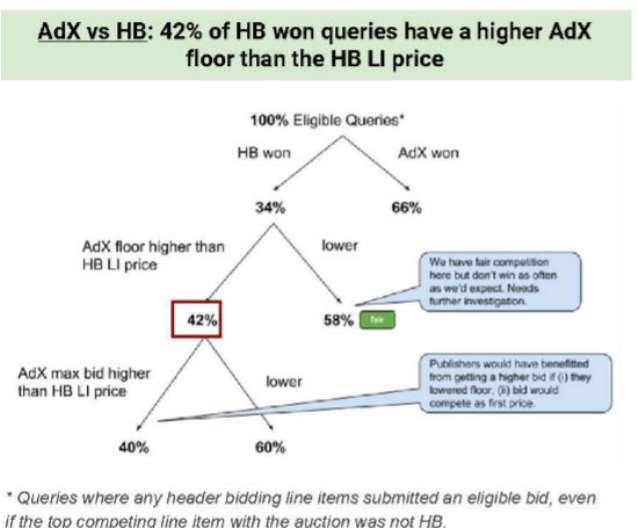

4

The process described herein governs the sale of display ads on the “open web,” meaning

websites whose inventory is sold through ad tech intermediaries that offer inventory from

16

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 21 of 153 PageID# 21

displayed on

a website that is

viewed in an internet browser is called

a display ad. A display ad

may

contain images, text, or multimedia. A single

display

ad shown to a single user

on a single

occasion

is called

an

impression.

44.

An ad tech transaction

begins when a user opens a

website. While the website’s

content loads, the

website uses

a

publisher ad server

to select which ads

will fill each ad slot on

the page. The publisher ad server is an ad tech tool that

evaluates

potential

ads from different

advertising sources

and

applies

a

decision-making logic

to

determine which ad will be displayed

to the user opening the website. Since 2008, Google

has owned t

he industry’s leading publisher

ad server, Google Ad Manager, which is often still referred to by its former name,

DoubleClick

for Publishers (“DFP”).

45.

For a typical medium-to-large website, the publisher

ad server first determines

whether the ad spaces

on the

webpage

opened by the user have

already

been sold to a specific

advertiser directly by the

publisher. Such

direct sales

result from one-on-one negotiations

between

website publishers and advertisers

and typically involve

premium

ad placements (e.g.,

ads at the top of a webpage) that command the

highest

prices

from advertisers.

For any ad space

not filled through

direct sales, the

publisher

ad server then tries to sell the ad

space through

indirect sales channels.

Indirect sales

allow

publishers

to sell

remaining or “remnant” ad space

multiple websites. Some websites, especially social media companies like Facebook and

Snapchat, operate under a different “closed web” (or “walled garden”) model in which inventory

is sold directly to individual advertisers using a proprietary tool employed by that website. Other

types of advertising distinct from open web display advertising include search ads (e.g.,

sponsored results in a search engine), video ads (e.g., commercials that play before, during, or

after a streaming video), and mobile app ads (e.g., ads shown within a game or other non-

browser app downloaded from an app store to a user’s mobile device). The focus of this

Complaint is on Google’s anticompetitive conduct in the market for open web display

advertising transactions.

17

5

For both direct and indirect sales, ad impressions are generally priced on a CPM basis,

referring to cost-per-thousand (in Latin, “mille”) per impression. For example, an impression

with a $1 CPM would cost $0.001, or one-tenth of a cent.

6

Because the publisher ad server historically transmitted this information to the ad exchange, the

publisher ad server controlled what information was sent to prospective advertisers and in what

form.

7

Information concerning t he user’s location and browsing history can be gleaned through

“cookies” set in place by the user’s web browser. These cookies allow the web browser to collect

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 22 of 153 PageID# 22

(i.e., space not sold through direct sales). Many website publishers, especially smaller ones, only

sell ad space through such indirect sales.

5

46. Indirect sales are typically made via a series of interactions between ad tech tools.

These technologies allow website publishers and advertisers to transact through lightning-fast

automated processes, known as programmatic buying. Today, most programmatic transactions

take place on an ad exchange. An ad exchange (sometimes called a supply-side platform or SSP)

is a software platform that receives requests—often from a publisher ad server—to auction ad

impressions on a particular webpage. The ad exchange solicits bids on the impression from

advertiser buying tools, chooses the winning bid, and transmits information on the winning bid

back to the publisher ad server. Google presently owns the industry’s leading ad exchange, called

AdX (now packaged as part of Google Ad Manager).

47. When a publisher ad server sends an auction request to an ad exchange, the

publisher ad server provides certain information about the impression for sale. This can include

information about the website itself, the ad space on the webpage (e.g., where the ad is placed),

and the user that will view the impression.

6

After receiving this information from the publisher

ad server, the ad exchange may supplement the information with any additional information the

ad exchange might independently have about the user viewing the ad, including information

about the user’s browsing history, location, and age.

7

The ad exchange then transmits the bid

18

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 23 of 153 PageID# 23

request, along with information gathered

about the user and the website,

to

various

advertiser

buying tools, described below. The detailed information c

oncerning the user’s location and

browsing

history is highly

valuable to advertisers

because it helps

advertisers

assess the value of

the

particular

impression to its

overall

advertising campaign. For example, if

the

information

tells a

particular

retail advertiser

that the user had previously browsed that retailer’s website but

did not complete a sale, then that retailer may be

willing to pay a premium for the particular

impression.

48.

Advertisers receive and respond to bid requests using

advertiser buying tools.

These advertiser buying tools assist advertisers with connecting to ad exchanges, selecting

impressions to bid on, submitting bids, and tracking

the purchased impressions

against the

advertiser’s advertising campaign goals.

49.

Large

ad buyers, such as

major ad agencies or large businesses, frequently

use a

type of

advertiser buying tool called a

demand side platform. Demand side platforms provide

sophisticated and customizable tools that

allow

the ad agency or business

to manage their

advertising purchases. Advertisers using

demand side platforms

have

extensive control over

where

and how they bid for ad inventory. They often use their own data, or

data purchased from

other entities, to target particular users

for their

ad

campaign.

Google owns the United States’

leading demand side platform, Display & Video 360 (“DV360”).

50.

Smaller advertisers

often

rely on

a type of advertiser

buying tool

with fewer,

simpler options

that are less customized. These advertiser buying tools

are called

advertiser ad

information about a user’s internet location and browsing history which can then be passed

along, or sold, to interested parties.

19

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 24 of 153 PageID# 24

networks.

8

Today, most ad networks bid for and buy advertising space on an impression-by-

impression basis, submitting bids alongside other ad networks and demand side platforms.

Advertiser ad networks offer a self-service, easy-to-use technology solution, which as a practical

matter is the only viable option for smaller advertisers, advertisers that prefer a simple “hands-

off” approach, or advertisers that need the ad network’s targeting data to buy ads effectively.

Google offers the industry’s leading ad network, Google Ads.

51. Most ad networks, including Google Ads, are a “black box” to advertisers.

Advertisers have almost no control over the process by which the ad network bids for

impressions. Nor do the networks provide advertisers with information about how or why the

network bids for particular impressions on particular websites at particular times. Most ad

networks charge advertisers primarily on a “cost per click,” or “CPC” basis. The advertiser thus

has no insight into how much the ad network spent to purchase a particular impression; the

advertiser is charged a fee only when an internet user clicks on the ad. Google’s ad network,

Google Ads, sets this fee based on the actual cost incurred to buy advertising inventory plus a

markup. This prevents Google’s advertising customers from knowing how much Google is

charging them, over and above Google’s costs, for the inventory.

52. These ad networks are particularly important to businesses that do not have the

expertise, advertising budget, or targeting data required for a demand side platform to be a viable

option. Ad networks are also critical to website publishers. These ad networks are the only way

for publishers to reach and sell ad space to smaller businesses that rely exclusively or primarily

8

These advertiser networks are referred to as “networks” because they originally operated on a

network model whereby the ad network would agree to buy a portion of a publisher’s advertising

space in bulk at a pre-set price. The ad network would then distribute the publisher’s advertising

space among a network of advertisers. The prices charged to those advertisers were not

necessarily derived from the bulk price the network paid to acquire the space.

20

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 25 of 153 PageID# 25

on ad networks to buy ad space. Further, the type of advertising space these ad networks seek to

purchase from website publishers is often distinct from the advertising space sought by other

advertising tools. That is because the advertisers using these networks often have unique

advertising objectives. Further, these ad networks, and in particular Google Ads, have access to

unique user data that allow them to target very specific advertising opportunities.

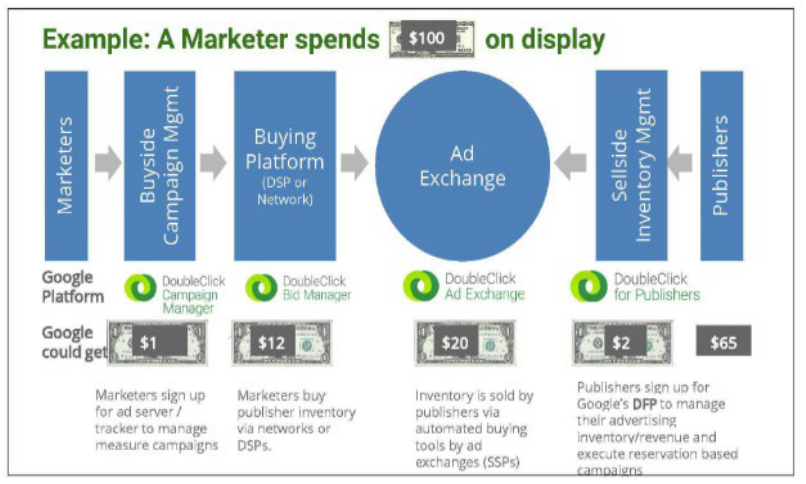

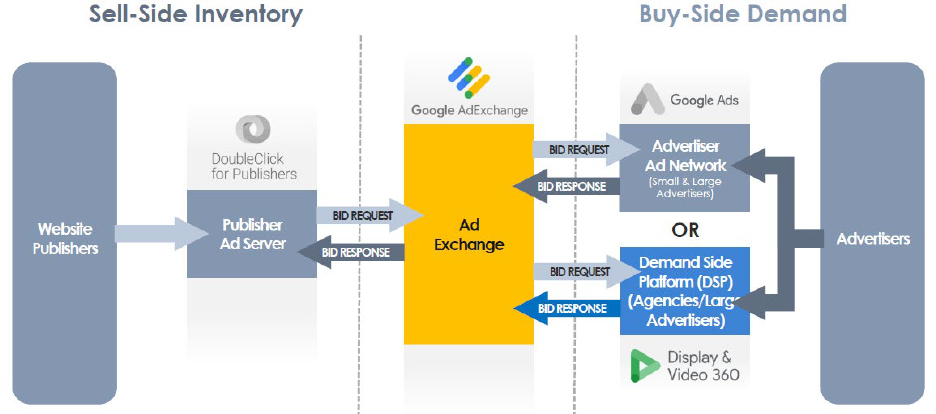

53. The flow of display ad transactions through these platforms—collectively called

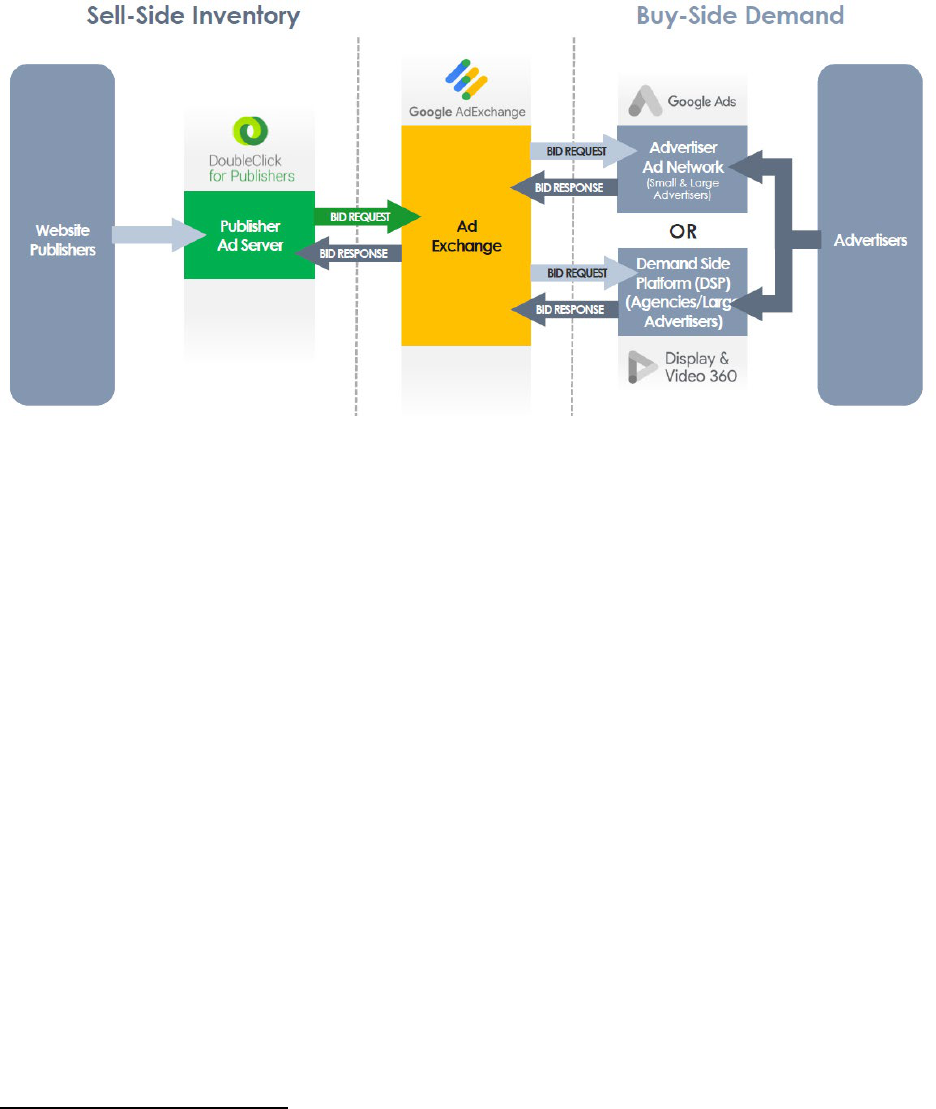

the ad tech stack—is depicted again below.

Fig. 3

54. The publisher ad server is referred to as the “sell-side.” The advertiser buying

tools are referred to as the “buy-side.” Impressions offered for sale by publishers are referred to

as publisher “inventory” and advertisers’ interest in buying impressions is referred to as

advertiser “demand.”

55. Whether the advertiser uses a demand side platform or an ad network as its

advertiser buying tool, the tool evaluates the bid request received from the ad exchange and, if

the impression meets the advertiser’s criteria (e.g., targeted audience, website category), the tool

21

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 26 of 153 PageID# 26

determines an amount to bid on the impression. Because each impression is filled within

fractions of a second while the website loads for the user, an advertiser could never evaluate each

impression individually. Instead, advertisers rely on these automated advertiser buying tools to

evaluate impressions and bid on their behalf based on parameters pre-configured by the

advertiser ahead of time. The advertiser buying tool then sends its highest bid for the

impression—as calculated by the tool—back to the ad exchange for consideration.

56. After receiving bids from multiple advertiser buying tools, the ad exchange holds

an auction to determine the winning bidder. Historically, most ad exchanges ran a second-price

auction in which the winning bidder paid a price one cent higher than the bid of the second-

highest bidder. Today, however, most ad exchanges run first-price auctions where the highest

bidder simply pays the price of its winning bid. The ad exchange sends information about its

winning bid back to the publisher ad server, which evaluates the ad exchange’s bid under a set of

rules defined by the publisher ad server. The publisher ad server then makes the final decision

regarding which ad to “serve” to the user. The publisher ad server sends a message to the

winning advertiser to provide the content of the ad to be displayed.

B. How Ad Tech Intermediaries Get Paid

57. Once the winning bid has been chosen, the advertiser pays the website publisher

for the impression, but a portion of the payment is retained by each intermediary along the way

as payment for its services. The advertiser buying tool and the ad exchange supplying the

winning bid each collect a portion of the purchase price for the impression, which is referred to

as a “revenue share” or “take rate.” The publisher ad server generally charges the publisher a

fee based on the number of impressions served. Unlike a revenue share, the publisher ad server

fee typically does not vary based upon the price paid for each particular impression.

22

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 27 of 153 PageID# 27

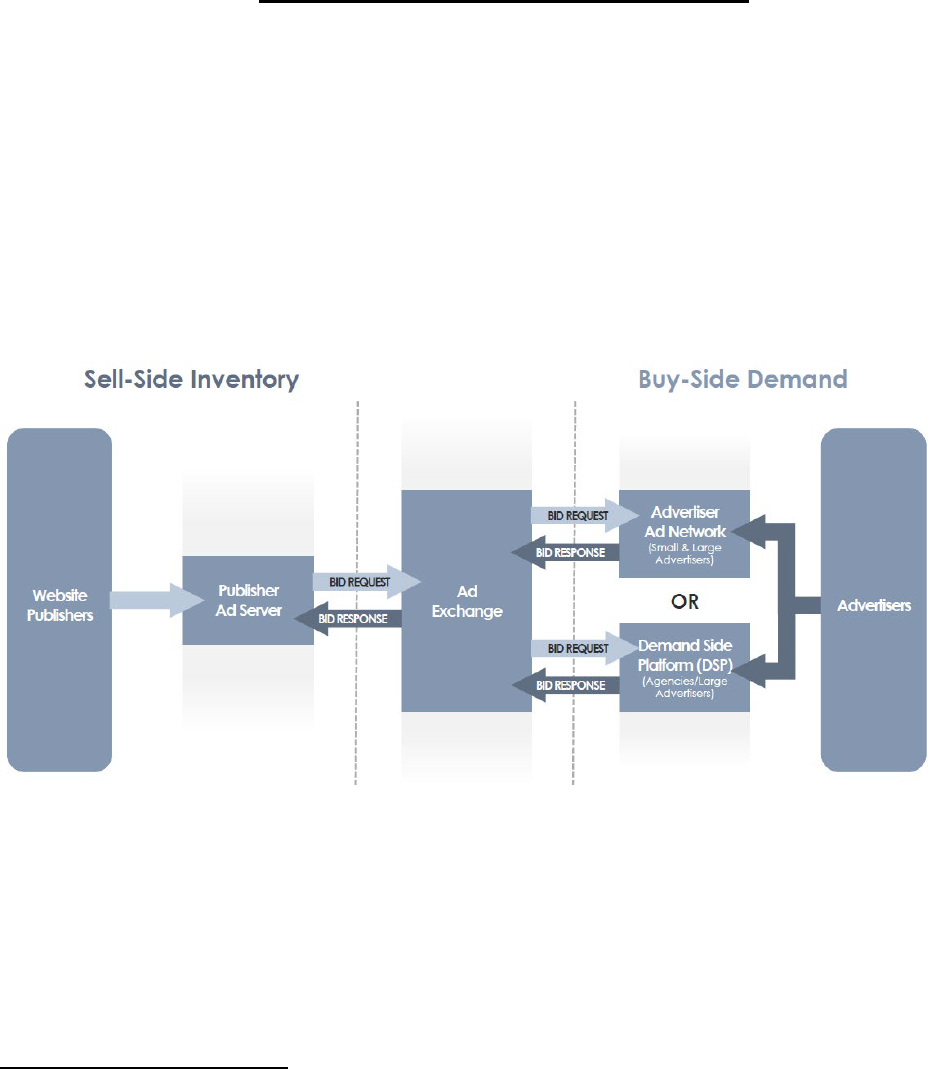

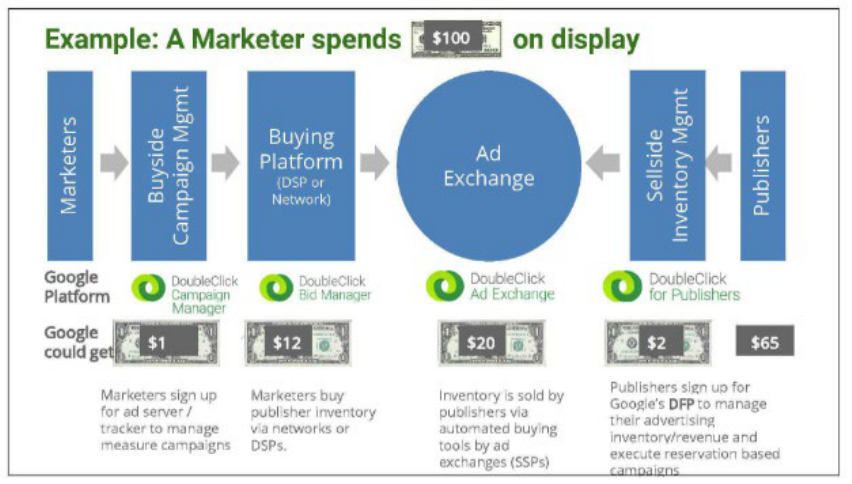

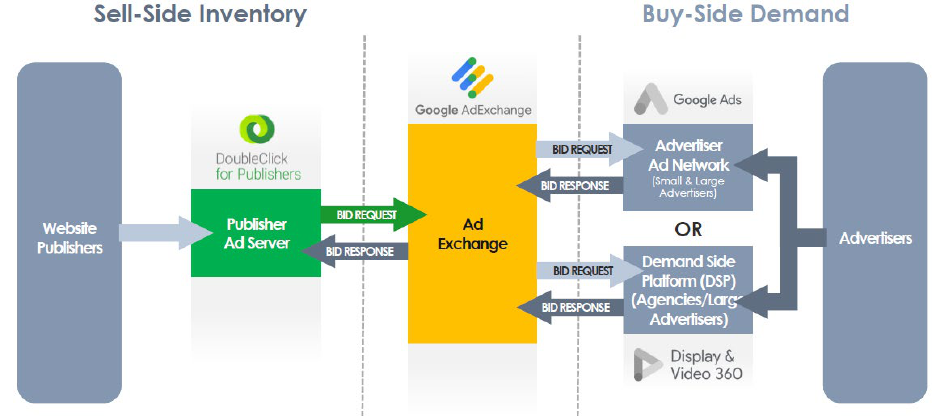

58. The total percentage of advertiser spend extracted by ad tech intermediaries can

have a substantial impact on the revenue website publishers earn from advertising and on the

return on investment that advertisers receive from their advertising campaigns. But this

percentage is typically not fully transparent to advertisers or publishers; some fees are disclosed

only to publishers or advertisers while other fees are obscured or not disclosed at all. According

to Google’s internal documents, when a transaction passes through each of Google’s ad tech

tools (including Google’s campaign manager product, which helps advertisers manage ad content

and track campaign spending), Google estimates that it gets to keep about 35% of every dollar

spent on digital advertising (as shown in Figure 4 below).

Fig. 4

59. These technology platforms have provided essentially the same services for over a

decade. During that time, Google’s monopoly positions and the restrictions it has imposed across

these technologies have diminished the incentive and ability for Google or others to innovate.

This reduced innovation is compounded by high prices: despite publishers’ and advertisers’

23

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 28 of 153 PageID# 28

interests in reducing the amount of advertising spending siphoned off by intermediaries,

Google’s take rate has remained remarkably stable over time. In particular, Google has

consistently charged a roughly 20% fee for impressions bought through its ad exchange, the link

in the chain where the highest fees are charged.

C. How Publishers and Advertisers Select Ad Tech Tools

60. Publishers and advertisers try to optimize their use of ad tech to meet their

revenue or advertising goals. As a general matter, publishers use only one publisher ad server to

manage ad inventory in order to avoid discrepancies in tracking revenue or impressions and to

minimize the burden of having employees oversee two largely duplicative systems. Ultimately,

there can only be one publisher ad server acting as the final decision-maker as to which

advertisement will fill each impression.

61. Sizeable publishers generally prefer to offer their inventory for sale through more

than one ad exchange (a practice called “multi-homing”). This increases the likelihood that an

advertiser on one or more of the ad exchanges will be able to “match” the advertising

opportunity offered by the publisher to a user or category of user that an advertiser particularly

values and therefore is willing to compete to buy. When publishers are able to offer their

inventory for sale through multiple ad exchanges simultaneously, it causes ad exchanges to

compete with each other to provide the best “match” or the lowest revenue share. However, there

are integration, contracting, and other costs associated with the publisher adding each additional

ad exchange.

62. Likewise, advertisers often connect with multiple ad exchanges through their

advertiser buying tools, hoping that exposure to as much advertising inventory as possible will

increase the likelihood of reaching the advertisers’ intended targets for their advertising

campaigns at the lowest cost. Using multiple ad exchanges also allows advertisers to compare

24

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 29 of 153 PageID# 29

performance between ad exchanges. Similarly, when advertisers are able to freely multi-home

among ad exchanges, it forces ad exchanges to compete with each other to provide advertisers

the best return on their advertising expenditures.

63. Although there are a number of factors that advertisers consider when deciding

which ad exchanges and/or ad buying tools to use, one key driver is access to especially valuable

advertising inventory. Some ad tech products can be used to buy or sell both open web display

advertising—the focus of this Complaint—as well as other types of advertising, such as

advertising inventory that is “owned-and-operated” (“O&O”) by the company offering the ad

tech product.

64. For example, some of Google’s ad tech products allow advertisers to buy both

open web display advertising on third-party websites as well as advertising on Google’s O&O

properties. Google’s O&O properties include several market-leading sources of non-open web

display advertising inventory, such as Google Search, YouTube, Gmail, and Android’s Google

Play Store, among others. Advertisers and advertising agencies looking to advertise on these

O&O properties often must adopt at least one of Google’s advertising tools to do so effectively.

For example, many larger advertisers and ad agencies seeking to promote their brands through

online video advertising on the market-leading YouTube website generally must use Google’s

advertising tools to do so; so for them, as well, adoption of Google’s ad tech tools is considered a

must.

65. If an advertiser or advertising agency believes it needs Google’s tools for

purposes of Google O&O advertising, it is less likely to adopt another buying tool—or tools—to

advertise on the open web. Among other considerations, the adoption of multiple ad tech tools

typically costs more (in time and money) and limits the ability of the ad tech tools to share

25

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 30 of 153 PageID# 30

important performance data across these tools. As a result, companies with especially valuable

O&O advertising—such as Google—may be able to take advantage of existing, sizeable

advertising bases already locked into their advertising tools.

D. Why Scale and the Resulting Network Effects are Necessary to Compete in Ad

Tech

66. Scale is a critical factor in the long-term success of each of the key products that

comprise the ad tech stack. Scale and related network effects are cumulative; they reinforce

market power for incumbents and raise barriers to entry and competition for nascent and smaller

rivals. There are at least three important dimensions of scale at play in online digital display

advertising.

67. First, scale in ad tech means having a significant number and variety of publishers

or advertisers using a particular ad tech product. For example, an ad exchange that has

significant scale enjoys large numbers and varied types of (i) publisher advertising inventory, on

the one hand; and (ii) advertisers that bid through the ad exchange, on the other hand. This scale

is key to attracting both publishers and advertisers to the ad exchange because ad exchanges are

characterized by strong network effects (meaning that the value of an ad exchange to its users

increases as more users adopt the tool). An ad exchange with access to more inventory—

especially more sought-after inventory—will be more attractive to advertisers. Likewise, an ad

exchange with more advertisers—and more unique advertisers—will be more attractive to

publishers. This aspect of scale plays out in similar but less pronounced ways for publisher ad

servers. For example, larger and more valuable inventory justify an ad exchange incurring the

cost to integrate with a particular ad server. Publisher ad servers are also relatively more

expensive to build and relatively less expensive to run, so a larger publisher base allows the

publisher ad server to spread the fixed costs over more publishers. With respect to advertising

26

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 31 of 153 PageID# 31

buying tools, more advertisers and more overall advertising spend will attract publishers to a

particular tool. Moreover, to the extent that an advertiser buying tool has access to data from a

related sell-side product, the advertiser buying tool can gain unique targeting abilities.

68. Second, scale includes the number and quality of impressions that publishers have

offered for bidding through the ad tech product, the number of bids advertisers have made, and

the number of transactions that have been completed—as well as the associated revenue for those

transactions. The more business the ad tech provider has done, the more data that provider has,

and the greater the ability the provider has to increase the value of its services. For example, an

ad tech provider that is able to see a larger swath of advertising inventory made available for

auction will have greater insights into the universe of inventory available, and can adjust—or

suggest adjustments to—its customer’s bidding behavior accordingly. Additionally, an ad tech

provider that is able to see at scale who ultimately buys or bids on inventory and at what prices

can create bidding strategies that can be used to predict more accurately future auctions for

similar inventory. For example, the ability to observe the depth and distribution of bids for

different advertising inventory can provide valuable data on how demand might change based on

price and other factors. In addition, data concerning advertisers’ buying strategies, and how all of

this information changes over time, is incredibly useful. Without access to this type of inventory,

bidding, and transaction information at scale, an ad tech provider is less able to offer a

competitive ad tech tool to publishers or advertisers.

69. Third, scale includes the depth of targeting data that an ad tech product has

available and can use to identify the most valuable matches between particular pieces of

publisher inventory and advertisers. This aspect of scale in the ad tech ecosystem is influenced

both by an ad tech provider’s access to relevant targeting data from seeing and winning more

27

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 32 of 153 PageID# 32

digital advertising transactions (which can provide important information on an internet user’s

characteristics and behavior) as well as from other parts of its business (e.g., Google’s access to

website contextual data and detailed user profiles on its customers using Search, Chrome,

Android, or Gmail).

70. The ability of an ad tech product to achieve scale along these dimensions is

important to its long-term success. For an ad exchange, increasing publisher inventory and

advertiser demand, understanding the likely bid landscape based on prior consummated

transactions, and having access to detailed user targeting and contextual data all increase the ad

exchange’s chances of being the supplier of the advertiser bid ultimately selected by the

publisher ad server. This is key because ad exchanges only collect a revenue share on winning

bids—even though the ad exchange incurs costs (for personnel, equipment, and processing

power) for every bid request and response, whether won or lost. An ad exchange lacking

sufficient access to these various dimensions of scale may not be able to compete effectively,

innovate, or even operate.

E. How Multi-Homing Enables Competition in the Ad Tech Stack

71. The purpose of the ad tech stack is to bring together publishers and advertisers.

Publishers benefit when there are more advertisers to bid on their inventory, and advertisers

benefit when there are more impressions available to buy. As a result, the various markets that

make up the ad tech stack exhibit strong “indirect network effects,” i.e., the value of the services

provided by these ad tech tools increases as the number of participants on both sides of the

product increases.

72. Additionally, because each possible advertising opportunity (or impression) is

unique based on a variety of factors (e.g., the identity of the user, the substance of the website,

the location on the webpage), the value of a particular impression opportunity can vary

28

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 33 of 153 PageID# 33

significantly across advertisers. For example, a banner ad at the top of an automotive website

would be highly valuable to a car dealership located in the same zip code as the user; that same

banner ad space would be less valuable to a home improvement store located in another state.

Digital advertising technology, when operating in a healthy, competitive environment, attempts

to create the most value for its customers by matching publisher advertising opportunities with

the advertisers willing to pay the most for them. By multi-homing across ad exchanges, both

website publishers and advertisers are able not only to seek the best possible match for a given

advertising opportunity, they are also able to contribute to, and benefit from, competition more

generally.

73. Ad exchanges compete for publisher inventory and advertiser demand at two

distinct but related levels. First, they compete for adoption by publishers and advertisers, i.e., the

opportunity to see a publisher’s inventory or submit an advertiser’s bid. Second, once an

exchange has been adopted, it competes with other exchanges to win the ability to process a

particular advertising transaction (i.e., to win individual advertising auctions). At both levels of

competition, ad exchanges compete not only on price but also on quality and access. Generally,

an ad exchange with more advertisers will be more valuable to publishers, and vice versa. When

both sides in a market single-home (i.e., only connect with a single ad exchange), sellers

(publishers) tend to flock to the ad exchange with the most buyers (advertisers), all else being

equal. Advertisers likewise prefer the ad exchange that has the most advertising inventory from

publishers. Google’s dominance of scale on both sides of the ad tech stack thereby strengthens

Google’s dominance overall in the industry and weakens its rivals’ ability to compete.

Conversely, when participants on both sides actively multi-home, there may be multiple

exchanges that offer access to the other side of the market, applying competitive pressure to

29

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 34 of 153 PageID# 34

decrease fees or increase quality in order to win business. Thus, actions that impair the ability of

one or both sides to multi-home are invariably corrosive to competition.

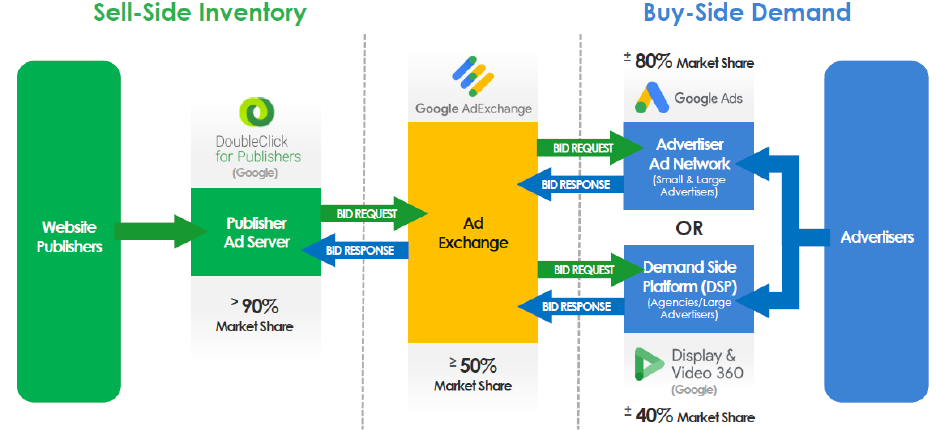

IV. GOOGLE’S SCHEME TO DOMINATE THE AD TECH STACK

74. Over the past fifteen years, Google has acquired and maintained mutually

reinforcing monopoly positions in tools across the ad tech stack. Google’s scheme has involved a

range of conduct, whereby it—often surreptitiously—has wielded its market power in various ad

tech tools to undermine attempts by publishers, advertisers, and rivals to introduce more

competition for digital advertising transactions. Individually and in the aggregate, Google’s

anticompetitive acts have deprived rivals of critical scale and contributed to Google’s dominance

by erecting substantial barriers to entry and competition.

75. Google also has used its dominant position time and again to prevent publishers—

its own customers—from efficiently and effectively multi-homing across ad exchanges, and to

prevent rival ad tech providers from deploying technology that would have improved the process

by which advertisers and publishers find the best advertising matches in real time for each

impression. In the face of potential competitive threats, Google has resisted innovation and

chosen not to compete on the merits. Instead, it has used acquisitions and market power across

adjacent ad tech markets to quash the rise of rivals, tighten its control over the manner and means

through which digital advertising transactions occur, and prevent publishers and advertisers from

30

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 35 of 153 PageID# 35

working effectively with Google’s rivals. As the figure below demonstrates, Google’s

dominance across the ad tech industry is unparalleled.

Fig. 5

A. Google Buys Control of the Key Tools that Link Publishers and Advertisers

76. Google entered display advertising on the back of its early strength in search and

search advertising. In 2000, Google launched Google Ads (then called “AdWords”), a self-

service buying tool for advertisers. At the time, advertisers could use Google Ads to purchase

advertising on the webpage displaying Google search results.

77. As Google’s search engine dominance grew, it attracted large numbers of small

and large businesses that considered advertising on Google’s search results page to be critical to

reaching customers searching for their products or services. After amassing this pool of

advertisers, Google realized it could not only sell them advertising space on Google’s search

results page, but also step in as an intermediary to sell them advertising space on non-Google

websites as well. Thus in 2003, Google changed the default setting on Google Ads so that

businesses were automatically opted into using Google Ads to advertise on third-party websites

31

Case 1:23-cv-00108 Document 1 Filed 01/24/23 Page 36 of 153 PageID# 36

through what became known as Google Display Network, or “GDN.” Today, Google Ads has

grown to represent over two million advertisers, spending about $11 billion worldwide on open

web display inventory per year. Google Ads is a substantial, unique source of advertising

demand and revenue for publishers.

78. In 2006, Google found itself without sufficient access to non-Google premium

advertising inventory to meet its advertisers’ demand. Effectively integrating Google Ads with

existing publisher-facing platforms would have benefited both Google Ads advertisers—by

increasing their access to inventory—and Google—by increasing advertising sales, and in turn

Google’s total revenues as a percentage of those sales. Instead, Google sought to maintain more

control over advertising purchases made by its Google Ads’ advertisers. In particular, it limited

the ability of its Google Ads’ advertisers to buy inventory from Google’s rivals. Google

recognized that if it could secure access to its own pool of publisher inventory, it could control

the entire transaction, end-to-end, and become the “the be-all, and end-all location for all ad

serving.” To that end, Google built and launched its own publisher ad server, but the product

failed to gain traction.

79. Rather than innovate and compete, Google found a shortcut. In 2007, Google

announced that it would buy DoubleClick for $3.1 billion. DoubleClick offered the industry-

leading publisher ad server, called DoubleClick for Publishers or “DFP”, which at the time had